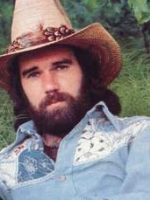

John Lincoln Wright Biography

For 25 years, John Lincoln Wright and The Sour Mash Boys have been the leading country act in Boston and New England. Wright has won every award from the Massachusetts Country Music Association so many times he's been retired from eligibility. His story is a bit different than most because Wright actually did "make it"once. In the late Sixties, singing rock music, young Wright had his first album reach Billboard's Top 100. But rock stardom was ultimately a very disillusioning experience. It soon became apparent that young Wright was a singer. "I couldn't say good-bye to Grandma until I sang a song. When I was 10, I won 25 cents singing 'All Shook Up' at a grammar school talent contest."

Like many kids, Wright became seriously interested in a music career when The Beatles "blew my head off." His band was doing well in Southern Maine until Wright began attending Boston College. By the time it fell apart, Wright had met a couple of new musical compatriots at BC. Their band lost its singer, and Wright joined on one day's notice. They came up with a new name, and the Beacon Street Union played its first gig at Salisbury Beach in the summer of 1966. "A year later, we had 19 record offers." They became the house band at Steve Paul's Scene, a trendy New York City club. "The audience would include Hendrix, Laura Nyro, a couple of Byrds, a couple of Doors. Whoever was in town. Hendrix sometimes came up and jammed with us."

The deal they signed, with MGM, turned out to be a mistake on two levels. Although "The Eyes Of The Beacon Street Union" reached Number 75 on Billboard, just about everyone hated it - including the band. "We played pretty well, but it doesn't show on the record. The album was rinky-dink.," says Wright now. He describes his voice on the album as "a Bee Gee on a bad day. I didn't think I sounded like that." Even worse was the critical backlash at MGM's now infamous "Bosstown Sound" advertising campaign, in which the Beacon Street Union were promoted in unison with Ultimate Spinach and Orpheus. None of the three acts sounded anything alike, and they didn't even know each other. Nor did the band get rich from the experience. "We signed one of the largest deals ever and never saw any money. The producer got it all."

A few years later, Wright found a new direction. "I was always aware of country music as something that was part of the mix. A guy we rented trucks from brought over a Merle Haggard tape. Suddenly it was 'My God, that's what I want to be doing'. I couldn't do Hendrix, Zeppelin, Cream anymore. I kept going hoarse during the first set." The last struggling vestige of Beacon Street Union started introducing songs like "Mama Tried" into its show. Finally, Wright went home. He spent six months in Maine writing country songs, some of which remain staples of his shows to this day. He came back to Boston in the summer of 1972, put an ad in the paper and formed his band. Then he heard about a small Harvard Square club that wanted to start having live music.

Before long, King's had lines around the corner. Wright's band was the hottest show in town. In 1975, things started changing. King's knocked down a wall and became the much larger Jonathan Swift's. And another local Sixties survivor, Willie Alexander, led the rise of "punk-rock" as the new hip musical thing. Nonetheless, the local country-rock scene continued to thrive. Swift's was packed every weekend for The Sour Mash Boys or other local acts like Wheatstraw and The Estes Boys. Meanwhile, Wright's group also traveled extensively in the Northeast, including frequent Big Apple appearances.During the band's first few years, there were constant rumors of imminent major label deals. Wright says most discussions never reached the offer stage. "There was a guy who said he could get us on to a label. He managed another act on that label. Some of my band knew some of his band. They called and were told 'He took all of our money and spent it at the racetrack. Stay away.' "We could have had a record deal with him, but it would not have been worthwhile."

Wright has had some other near misses. In 1980, Joe Sun - coming off a string of hits - covered "Lonesome Rainin' City" and "Pull Away From Your Man" on his third album, "Livin' On Honky Tonk Time." Neither cut was released as a single, and another Wright song Sun cut after moving to Elektra, "Lovin' In The Morning," went unreleased when Sun's career faded.Sun was popular in Europe. (He subsequently moved over there and continued to record.) So was Vernon Oxford, who cut "Lonesome Rainin' City" at around the same time Sun did. So was James Talley, who recorded four tracks with the Sour Mash Boys (co-produced by Wright) that were only released in Germany. Wright would have seemed to be a natural to develop a European following of his own, except that he never went. "I never had the money" is his simple explanation.

Wright has made numerous trips to Nashville in the past 25 years, to pitch his songs as well as himself. But he never moved down there, a commitment Nashville increasingly demands of its suitors. "I wasn't there. I wasn't in the loop," Wright admits, adding "I've always been a loner in this business. I'm not a schmoozer. The last time I went to Nashville for an extended period was 15 years ago. My last trip there was six years ago." Nothing happened either time. Nonetheless, he has managed to get out four albums and a bunch of singles and EPs. The two CDs, "Honky Tonk Verite" and the acoustic, very personal, "That Old Mill" remain available. The vinyl is all long gone, although Wright hopes to get his first two albums pressed onto CD eventually. He also plans to put out a new album next year. "I've got the songs. It'll be an adult album, a personal one. There'll be some hard-core country, but it won't be geared to the honky-tonk market. "

The New England country music scene is much smaller than in the seventies. Not only is there no place in Boston featuring country regularly, but many outlying clubs around New England have also disappeared."There's no circuit anymore," says Wright, who makes do now with scattered club gigs and things like corporate parties and municipal celebrations. "Bad luck and bad timing," Wright reflects on his long career. "I have disappointments. I'm struggling to make a living in diminished opportunities. I'm fundamentally a performer; I have to be on-stage. I've done it since I was a kid. But I have great satisfaction at what I've done professionally. I'm satisfied that I've learned what I do well. I regret I never took care of the business side of things - publishing, being more prolific as a songwriter, making regular albums." "I'd still like to find a three-album deal with a good independent label. Someone who'd let me make an album a year I have a lot of new songs that I haven't hustled. I'm not a businessman, I'm a singer."